Found to fixed: Beehiiv paywall bypass + leaked JWT token

A write-up of my experience with Beehiiv's bug bounty program.

Note: All of this is personal work, none of this is on behalf of my employer

I wanted to publish a small write-up on an experience I had discovering, reporting, and getting a pair of bugs, bypassing the paywall and being able to potentially impersonate other users, fixed in Beehiiv, a newsletter publishing platform. Shoutout to their team for solid communication and smooth process.

This post is intended for both a technical and a non-technical audience. It's meant to give a little bit of a behind-the-scenes look at how these sorts of thing are discovered and reported to the non-technical folks, and also provide the technical folks with some detail on working with Beehiiv’s bug bounty + responsible disclosure program.

Background

There are two important pieces of background information that are relevant here.

The first is that I spend much too much time reading online newsletters. I currently try to keep up with nearly 200 Substacks as well as an assortment of other folks that haven't (yet) been convinced to move over to the platform.

The second is that in a past life, I spent a lot of time scraping data. My last job consisted of finding disparate information all across the internet and trying to consolidate it in a regularly updated knowledge graph. As a part of that, I got pretty used to trying to see the internet as something machine-readable. I actually have a Chrome extension running at all times that flags and logs a bunch of behind-the-scenes ways that a browser and server trade data and sort of habitually read what it finds because I am weird enough to find this interesting.

A primer on APIs

For the non-technical folks, here is an overly simplified explanation of how a modern website works. If you're a developer of some kind, you can skip this section.

When you load a page, generally, what you're actually loading is a small subset of what you requested to see combined with instructions on how to load the rest of it. There are a number of reasons for this, but the easiest two to think about are:

It's much faster to do it this way

It lets you navigate around and change things on the page without having to fully reload

For example, when you load your Facebook, what you're likely actually loading is just the code that tells you how to display the data that you'll eventually get, and where to ask for data. Once that's loaded, your browser will make requests back to the servers for all the necessary data to display on that page. You might submit one for your timeline, one to load your notifications, another to load your chats and so on and so forth. It's possible that all of those requests are handled at the same time on totally different servers.

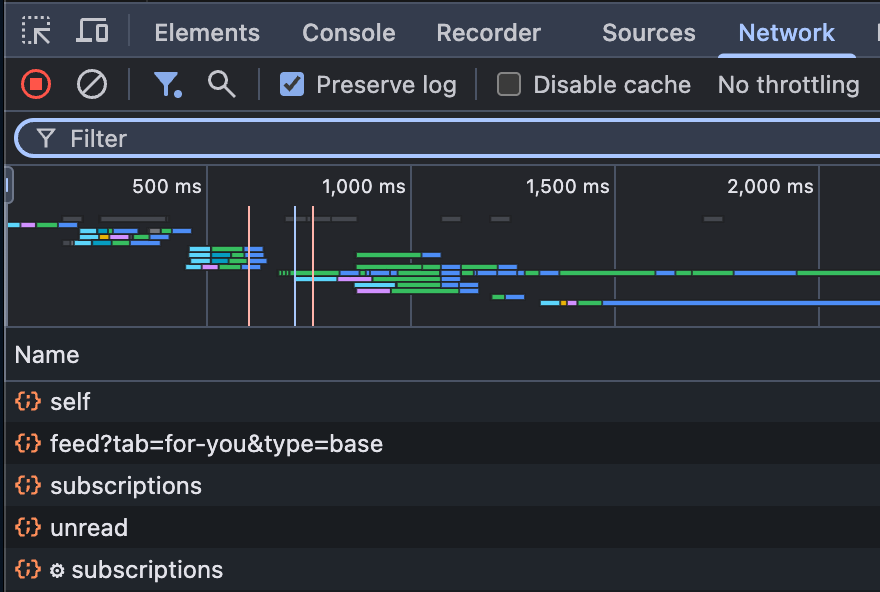

If you open up the developer tools in your browser, you can actually see these requests and responses come through in real-time and on a timeline.

For example, the below image is a subset of things that happen when I go to substack.com and load Notes. You can see we're separately fetching some information about myself (probably to render my profile picture and name), fetching Notes for my feed, information about my subscriptions, and how many notifications I have.

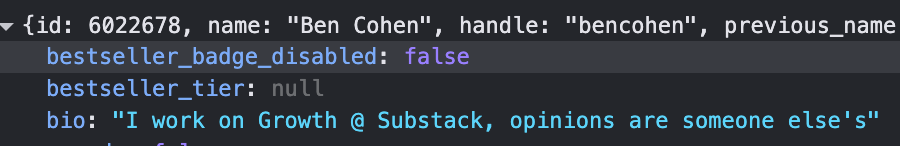

If you click on these, you can actually see what data is being requested and how it's being sent back in machine-readable form. For example, on that call to “self” endpoint, you can see a bunch of stuff that comes back: I have an ID, a name, a bio, and some stuff that you might not even know existed. This is data that is visible to machines, but often invisible to people. The security world has a disdain for what they call "security by obscurity” - best practices say that anything you put here should be non-sensitive, which is to say that it should never be a problem if someone like me is snooping and looking at all of this data. It's not stuff you expect all of your users to be reading at all times. But it shouldn't be a problem if any user sees anything in here.

To build some vocabulary, what my browser is doing here is hitting what's called an API, which is short for Application Programming Interface. An API is essentially a agreed-upon protocol for what format to ask questions in and what format answers will come back in.

You might have heard of an API before and even heard a discussion about whether or not a company has an API or not. You might even be saying, "Hey Ben, I thought Substack didn't have an API."

The answer is that there is a big difference between a public and a private API. A public API is something where it is encouraged for developers to be hitting it from automated applications. To support this, there is often published documentation and an agreement that it won't change very often.

A “private API”, like the ones shown above, are generally seen as for developers of the company only and therefore make no such promises about being intelligible nor static. Many huge companies like Facebook or Google spend a lot of time making sure these are nearly unintelligible and unusable to people trying to use them outside of the scope of their website, but most other places don't pay as much attention.

As an example of why these can’t be relied on, Substack could decide that /self is a bad name and change that endpoint to /me tomorrow. These endpoints can and often do change regularly, and it should never be assumed that what works today will work tomorrow, unlike a public API, which needs to remain constant so that other people can build stable software against it. When an API is private and there are no expected "customers", it becomes okay to rapidly change them as long as the "front-end code" of the website keeps up.

The other big difference between public and private APIs is how they handle entitlements. A public API has a key that you generate and an agreed-upon scope of what that key gets you access to. For example, Twitter might say, "Here is an API key that you can use to read tweets, but this key can't be used to post anything." Often, companies with mature API products will have multiple keys per account with different levels of entitlement - one key may be read only, another may be write only, etc.

A private API has less well-defined entitlements because there is no agreed-upon contract. With a private API, your browser is basically saying, "Here is authentication information you've given me in the form of cookies or something. Give me data." In a functional system, it's the server's job to decide if it's allowed to have that data or not. For example, when I call that /self endpoint above, it happily gives me information about my account, but if I try to call it for your account, I will get an error saying “you don’t have access to that, go away”

The first vulnerability

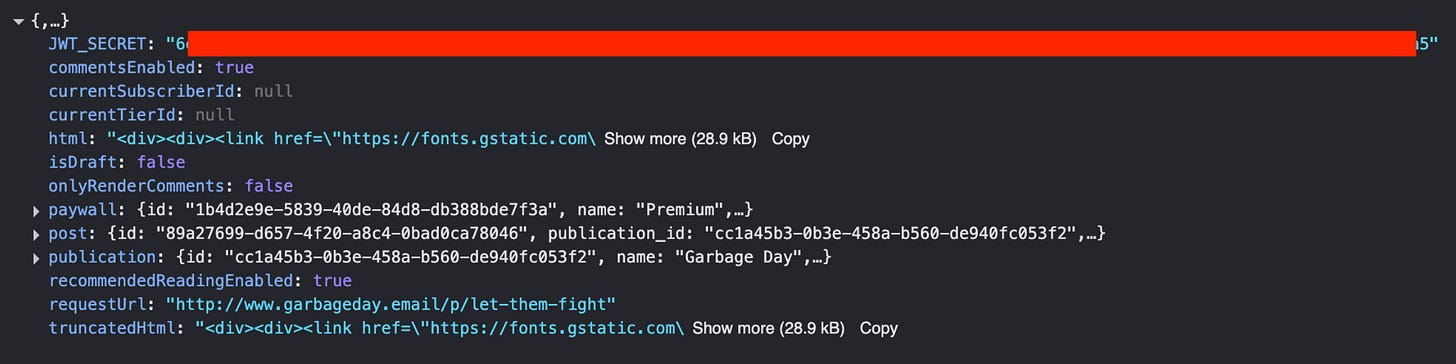

Anyways, the other morning I was on a newsletter on Beehiiv with my console open and half-habitually flicking through the API requests and half reading it, when something caught my eye in a response.

Generally, when you see something that is all caps and contains the word "secret", that is something that your users are not supposed to see. This piqued my interest, and I started poking around a little bit more to see what Beehiiv was doing with this information.

Secrets and Tokens

For a little more background, the concept of a secret key is that it is essentially a (long) password that a service uses to validate that data being sent to it is truthful. For example, as I mentioned above I can not say "Hey Substack, I am Ben Cohen, go fetch me the private profile information of Chris Best".

I also should not be able to say "Hey Substack, I am totally the real Chris Best, please give me my private information wink wink it’s me". To differentiate between the real Chris Best and me, the fake Chris Best, Substack uses a secret key like the above to cryptographically validate the data that is being sent back to it originated from its server, not from an impostor. If I tried to tell the server that I'm Chris Best, it will say, "Hey, wait a second. I did not generate this message telling you that you are Chris Best. You are not Chris, and you can't have that information."

If someone were to get a hold of a company’s secret key, they could generate messages/requests (e.g., "they are whoever they want to be") that the server would accept as truthful.

It's not unheard of for developers to sometimes unintentionally “leak” information in these API requests that the front end shouldn't have access to, and it seems like an instance of that was happening here. Servers are constantly passing around and using information that the end users don't have access to and it is sometimes tedious (but important!) to make sure that that information is properly redacted before sending it to the users.

The paywall bypass

After finding this potential vulnerability, I decided to poke around a little bit more. I saw a few other endpoints that my browser was hitting to load the post and information about the publication I was reading, including one that was

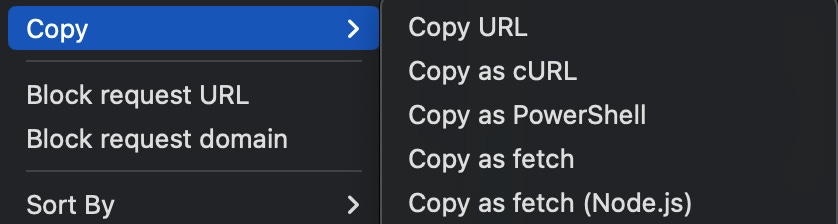

https://app.beehiiv.com/api/v2/posts/slug-of-some-postI noticed that this was passing my log-in information and information about the publication I was reading and the post I was trying to access. I spun up a Python notebook (basically an interactive way of quickly running/prototyping code) and put in the ID of a paywalled post that I didn't have access to and tried to make the same request. In your browser developer tools, you can actually right-click any request that's being made to the server and copy the information to make that request yourself from a different context should you want to do that.

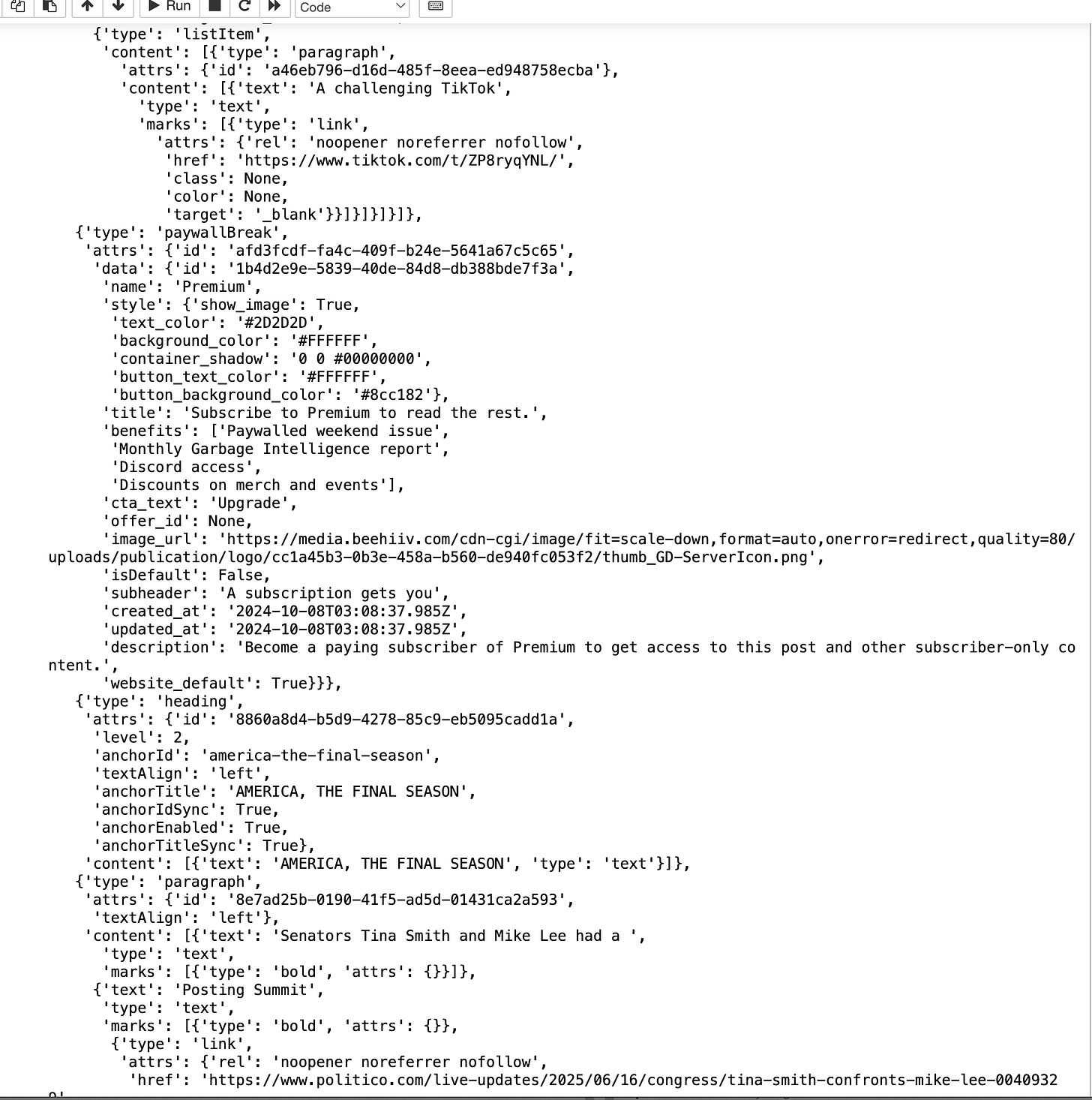

Lo and behold, something interesting came back. Not only did I get the machine-readable version of the post and where the paywall should go, but the server actually happily sent me the stuff behind the paywall!

This was another instance of "security by obscurity", where the server was relying on nobody reading the machine-digestible representation of what it sent back and relying on its own front-end code to properly truncate and show me the content that I'm entitled to.

Here is a (no longer functional) reproduction of the code to fetch the above post information:

import requests

headers = {

'authorization': 'Bearer $ANY WRITER TOKEN',

'user-agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/137.0.0.0 Safari/537.36',

}

params = {

# as far as I can tell, this needs to exist, but does not need to match the publication that the post belongs to. this points to my test pub

'publication_id': '9c6ce40a-1011-4093-a5bb-0cc8318dffd3',

}

response = requests.get('https://app.beehiiv.com/api/v2/posts/$ANY_POST_SLUG', params=params, headers=headers)The above code should have just given me the subsection of the post that I have access to, but instead always returned the entire post.

To annotate that a little bit, for non-developers, there are four things happening in that above block of code:

We're importing a module used to make web requests

We're defining some headers which are things that are sent up that are adjacent to the core request being made, The headers here are saying who I am - The authorization token is a token that the server gave me to represent being logged in as myself, and the user agent is information about my browser.

The parameters are defining what publication ID this post is for

The last line is sending a request to the server combining all of the above information to say "here is everything I'm telling you that I want, please give me information on this post"

In this case, given that my user should not have had access to this post, the correct thing for the server to respond was either an error code saying "you don't have access here" or a successful response with the truncated subset of the post that I do have access to. In theory, this would be usable to see behind the paywall for any post on the platform.

Response/Remediation + Timeline

At this point, I' decided to reach out to the Beehiiv team to do the industry standard process, which is called a "responsible disclosure". The gist of a responsible disclosure is that people often find vulnerabilities that could be very damaging if the company doesn't know about them.

For example, if you find a way to log in as a CEO of that company, a company would much rather know that before it gets into the hands of a bad actor. Generally, companies offer some sort of goodwill bounty as a thank you for responsibly disclosing bugs and not talking about them publicly until they are fixed.

On June 27, I emailed the Beehiiv privacy and security teams to let them know that I had a bug that I would like to responsibly disclose and to ask what their policy was. They responded on the 30th, outlining their policy, and I disclosed the above two bugs to them on June 30th.

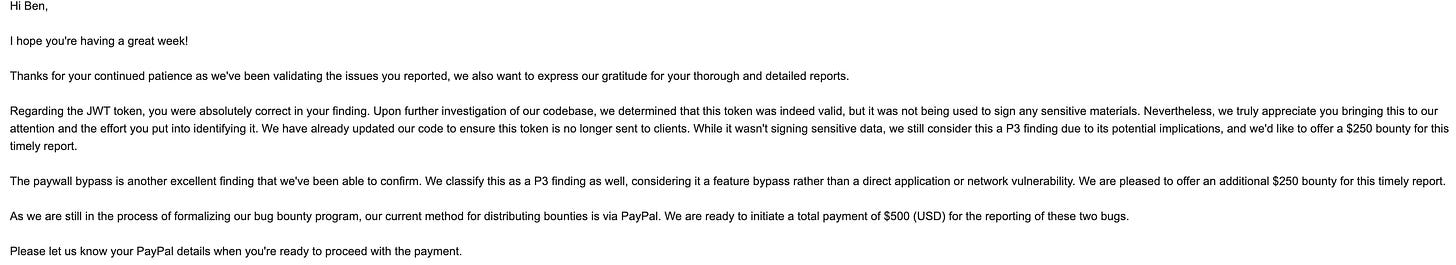

On July 14th, they responded that both bugs had been fixed. Their team decided that both bugs were P3 (low severity) bugs, due to reasons that they outlined in the below email. They were kind enough to offer a $250 bounty for each of the bugs, which they paid quickly and immediately to me after getting my information.

After getting the above email, I confirmed that both bugs had in fact been fixed and were now inaccessible to end users and wrote up this post (then waited a month and a half to click “publish”, as one does).

The end

I hope this was a useful brief look into how some websites behind the scenes as well as how the industry operates around disclosing bugs and vulnerabilities.

I want to give another shout out to the Beehiiv team who was communicative, thankful, and generous throughout the disclosure process.

Super interesting to a non technical person like me! Thanks for explaining it. Also you’re a good person.